Finite fields are one thing and elliptic curves another. We can combine them by defining an elliptic curve over a finite field. All the equations for an elliptic curve work over a finite field. By “work”, we mean that we can do the same addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division as defined in a particular finite field and all the equations stay true. If this sounds confusing, it is. Abstract algebra is abstract!

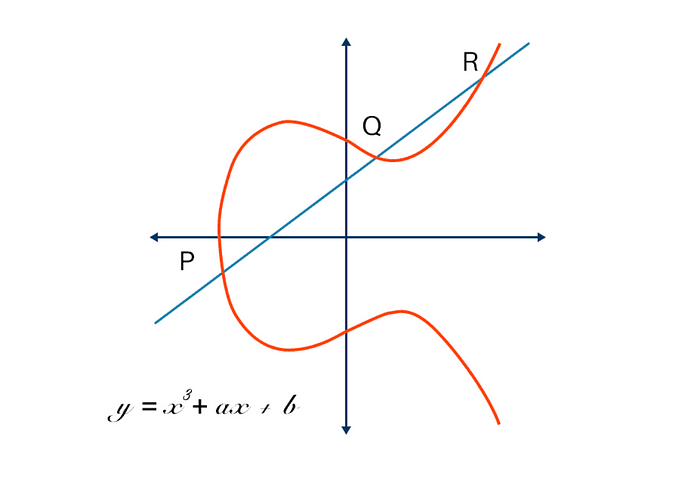

Of course, the elliptic curve graphed over a finite field looks very different than an actual elliptic curve graphed over the Reals. An elliptic curve over real numbers looks like this:

How to calculate Elliptic Curves over Finite Fields

Let’s look at how this works. We can confirm that (73, 128) is on the curve y2=x3+7 over the finite field F137.

$ python2

>>> 128**2 % 137

81

>>> (73**3 + 7) % 137

81The left side of the equation (y2) is handled exactly the same as in a finite field. That is, we do field multiplication of y * y. The right side is done the same way and we get the same value.

EXERCISE

True or False: Point is on the y2=x3+7 curve over F223

- (192, 105)

2. (17, 56)

3. (200, 119)

4. (1, 193)

5. (42, 99)

answer: check the end of this article (1)

Group Law

The group law for an elliptic curve also works over a finite field:

Curve:y2=x3+ax+b

P1=(x1,y1) P2=(x2,y2) P1+P2=(x3,y3)

When x1≠x2:

s=(y2-y1)/(x2-x1)

x3=s2-x1-x2

y3=s(x1-x3)-y1

The above equation is used to find the third point that intersects the curve given two other points on the curve. In a finite field, this still holds true, though not as intuitively since the graph is a large scattershot. Essentially, all of these equations work in a finite field. Let’s see in an example:

Curve: y2=x3+7

Field: F137

P1 = (73, 128) P2 = (46, 22)

Find P1+P2

First, we can confirm both points are on the curve:

1282% 137 = 81 = (733+7) % 137

222% 137 = 73 = (463+7) % 137

Now we apply the formula above:

s = (y2-y1)/(x2-x1) = (22–128)/(46–73) = 106/27

To get 1/27, we have to use field division as we learned last time.

PYTHON:

>>> pow(27, 135, 137)

66

>>> (106*66) % 137

9We get s=106/27=106*66 % 137=9. Now we can calculate the rest:

x3 = s2-x1-x2 = 92–46–73 = 99

y3 = s(x1-x3)-y1 = 9(73–99)-128 = 49

We can confirm that this is on the curve:

492% 137 = 72 = (993+7) % 137

P1+P2 = (99, 49)

EXERCISE

Calculate the following on the curve: y2=x3+7 over F223

- (192, 105) + (17, 56)

2. (47, 71) + (117, 141)

3. (143, 98) + (76, 66)

answer: check the end of this article (2)

Using the Group Law

Given a point on the curve, G, we can create a nice finite group. A group, remember, is a set of numbers closed under a single operation that’s associative, commutative, invertible, and has an identity.

We produce this group, by adding the point to itself. We can call that point 2G. We can add G again to get 3G, 4G, and so on. We do this until we get to some nG where nG=0. This set of points {0, G, 2G, 3G, 4G, … (n-1)G} is a mathematical group. 0, by the way, is the “point at infinity”. You get this point by adding (x,y) + (x,-y). Given that (x,y) is on the curve (x,-y) is on the curve since the left side of the elliptic curve equation has a y2. Adding these produces a point that’s got infinity for both x and y. This is what we call identity.

It turns out that calculating sG = P is pretty easy, but given G and P, it’s difficult to calculate s without checking every possible number from 1 to n-1. This is called the Discrete Log problem and it’s very hard to go backward if n is really large. This s is what we call the secret key.

Because the field is finite, the group is also finite. What’s more, if we choose the elliptic curve and the prime number of the field carefully, we can also make the group have a large prime number of elements. Indeed, that’s what defines an elliptic curve for the purposes of elliptic curve cryptography.

Defining a Curve

Specifically, each ECC curve defines:

- elliptic curve equation

(usually defined as a and b in the equation y2 = x3 + ax + b) - p = Finite Field Prime Number

- G = Generator point

- n = prime number of points in the group

The curve used in Bitcoin is called secp256k1 and it has these parameters:

- Equation y2 = x3 + 7 (a = 0, b = 7)

- Prime Field (p) = 2256–232–977

- Base point (G) = (79BE667EF9DCBBAC55A06295CE870B07029BFCDB2DCE28D959F2815B16F81798, 483ADA7726A3C4655DA4FBFC0E1108A8FD17B448A68554199C47D08FFB10D4B8)

- Order (n) = FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFEBAAEDCE6AF48A03BBFD25E8CD0364141

The curve’s name is secp256k1, where SEC stands for Standards for Efficient Cryptography and 256 is the number of bits in the prime field.

The big thing to note about this curve is that n is fairly close to p. That is, most points on the curve are in the group. This is not necessarily a property shared in other curves. As a result, we have something pretty close to 2256 possible secret keys.

How Big Is 2256?

Note that 2256 is a really large number. It’s around 1077, which is way more than the number of atoms in our galaxy (1057). It’s basically inconceivable to calculate all possible secret keys as there are simply too many of them. A trillion computers doing a trillion operations every picosecond (10–12 seconds) for a trillion years is still less than 1056 operations.

Human intuition breaks down when it comes to numbers this big, perhaps because until recently we’ve never had a reason to think like this; if you’re thinking that all you need is more/faster computers, the numbers above haven’t sunk in.

Working With Elliptic Curves

To begin working with elliptic curves, let’s confirm that the generator point (G) is on the curve (y2 = x3 + 7)

G = (79BE667EF9DCBBAC55A06295CE870B07029BFCDB2DCE28D959F2815B16F81798, 483ADA7726A3C4655DA4FBFC0E1108A8FD17B448A68554199C47D08FFB10D4B8)

p = 2256–232–977

y2 = x3 + 7

$ python2

>>> x = 0x79BE667EF9DCBBAC55A06295CE870B07029BFCDB2DCE28D959F2815B16F81798

>>> y = 0x483ADA7726A3C4655DA4FBFC0E1108A8FD17B448A68554199C47D08FFB10D4B8

>>> p = 2**256 - 2**32 - 977

>>> y**2 % p == (x**3 + 7) % p

TrueRemember, we’re always working in the Prime Field of p. This means that we always mod p for these operations.

Next, let’s confirm that G has order n. That is, nG = 1. This is going to require the use of a python library called pycoin. It has all of the secp256k1 curve parameters that we can check. Similar libraries exist for other languages. Note that the actual process is a bit more complicated and the reader is encouraged to explore the implementation for more details.

G = (79BE667EF9DCBBAC55A06295CE870B07029BFCDB2DCE28D959F2815B16F81798, 483ADA7726A3C4655DA4FBFC0E1108A8FD17B448A68554199C47D08FFB10D4B8)

n = FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFEBAAEDCE6AF48A03BBFD25E8CD0364141

$ python2:

>>> n = 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFEBAAEDCE6AF48A03BBFD25E8CD0364141

>>> from pycoin.ecdsa import generator_secp256k1 as g

>>> (n*g).pair()

(None, None)(None, None) is actually the point at infinity, or the identity for point-addition.

Utilizing ECC for Public Key Cryptography

Private keys are the scalars, usually donated with “s” or some other lower case letter. The public key is the resulting point of the scalar multiplication or sG, which is usually denoted with “P”. P is actually a point on the curve and is thus two numbers, the x and y coordinate or (x,y).

Here’s how you can derive the public key from the private key:

PYTHON:

>>> from pycoin.ecdsa import generator_secp256k1 as g

>>> secret = 999

>>> x, y = (secret*g).pair()

>>> print(hex(x), hex(y))

('0x9680241112d370b56da22eb535745d9e314380e568229e09f7241066003bc471L', '0xddac2d377f03c201ffa0419d6596d10327d6c70313bb492ff495f946285d8f38L')

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Answer (1): 1. True, 2. True, 3. False, 4. True, 5. False

Answer (2): 1. (170, 142), 2. (60, 139), 3. (47, 71)